The Psychology of Price

The way we think influences the way we behave. This applies to buyers and sellers.

This piece on the psychology of price will make the way you deal with pricing easier, more enjoyable and more effective.

Whenever we think about dealing with price lots of issues come to mind.

The focus of this piece is on how people think about price and how that impacts on the buying process.

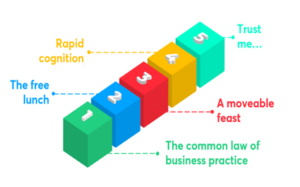

The Common Law of Business Balance

The “common law of business practice” is attributed to John Ruskin the 19th Century thinker, art historian and social commentator. It’s a great reminder about the principle of price.

“There is hardly anything in the world that someone cannot make a little worse and sell a little cheaper, and the people who consider price alone are that person’s lawful prey.

It’s unwise to pay too much, but it’s worse to pay too little. When you pay too much, you lose a little money — that is all.

When you pay too little, you sometimes lose everything, because the thing you bought was incapable of doing the thing it was bought to do.

The common law of business balance prohibits paying a little and getting a lot — it can’t be done.

If you deal with the lowest bidder, it is well to add something for the risk you run, and if you do that you will have enough to pay for something better.”

The Free Lunch

Brazilian author Paulo Coelho puts it like this:

“Be ready to pay the price of your dreams. Free cheese can only be found in a mousetrap.”

Or to put it another way “if it seems too good to be true it probably isn’t true!”

A Moveable Feast

The way we think about price is rarely constant.

It varies with time. Don’t think that just because a price was easily accepted last year it will be accepted this year.

It changes with the context: What seems to be an OK price when things are going well, may seem expensive in tough times. Our attitude to price is driven by our confidence. If we are optimistic about the future something may well seem to be easily affordable but too expensive if our income is reducing or fragile.

It depends with what we are comparing the price. Whenever anyone indicates “that’s expensive”, they are making a comparison. It could any one of these comparisons:

- A like-for-like firm offer already on my desk

- A price of a similar but different offer

- A price I’m hoping for from someone else

- What I pad last time

- My budget

- What I am hoping to pay

- What someone else paid for something similar

- What someone else told me they paid

- What my web searches and network tell me I could/should pay

- The price I want to end up paying

Rapid Cognition

Malcolm Gladwell in his excellent book “Blink” explains that we make many instantaneous decisions. Our response to price is often instantaneous but that doesn’t mean it’s not rational.

We often use “rapid cognition” to decide whether something seems too expensive.

“There are moments, particularly in times of stress, when haste does not make waste, when our snap judgements and first impressions can offer a much better means of making sense of the world” Malcolm Gladwell.

Trust me!

Our attitude to price is defined by the trust context. We may trust a supplier who we have found to be fair in their pricing in the past. Maybe they have demanded a high price but have delivered good value so we trust them again in this instance even though their price is high.

We also trust on price according to their personal, professional & corporate reputation. We may expect a lawyer’s fee to be higher than we would like because of their professional reputation. We may expect to pay more for a flight with a national carrier than with a budget airline. We may expect an individual to quote a higher rate because of their stature or reputation.

As Rachel Botsman (on of the leading thinkers on trust) writes in “Who Can You Trust”:

“I’m fascinated by how trust enables us to navigate uncertainty, place our faith in people and take leaps into the unknown.”

Stephen Covey Jnr speaks of a “trust tax” and a “trust dividend”. When trust is low every aspect of the price may be scrutinised and challenged. When trust is high there is often more acceptance that there will be mutual gain even if some elements of the price seem high. When it comes to assessing price the starting point for our trust is driven by personal, professional & corporate reputation and past experience. We must always consider the trust context when looking at price.

Trust is an essential aspect of how we and our customers think about trust. Trust is not random but is a manageable process.

Scarcity

Price is affected by scarcity

We know the laws of supply and demand. Don’t be surprised when scarcity or a glut impacts on your pricing. Be ahead of the curve especially if you are in a cyclical industry such as insurance or paper-making!

Intensity

It is driven by the intensity of our need or want

They say you should never go food shopping when you are hungry – you always pay more. A friend recently explained that, caught in the rain, he paid over the odds for a raincoat in London’s Jermyn Street. Need and want reduce price sensitivity!

Logic and emotion

Of course, the way people react to price has a logical, analytical side to it. But we ignore emotion at our peril. Believing one is being over-charged for a piece of work may involve an analysis of the hourly rate. It may also involve the sense that one is being cheated by someone who is taking advantage of a situation.

Pressure makes a difference

When we are under pressure our attitude to price changes. A salesperson who is ahead of target and who is asked for a discount may well defend the price more robustly than the colleague who needs the deal to get over the line or keep their job.

Conclusions on the psychology of price

The way we think about price will impact on the way we act and react when dealing with price. These five aspects of the psychology of price handling underpin the practices of price handling.